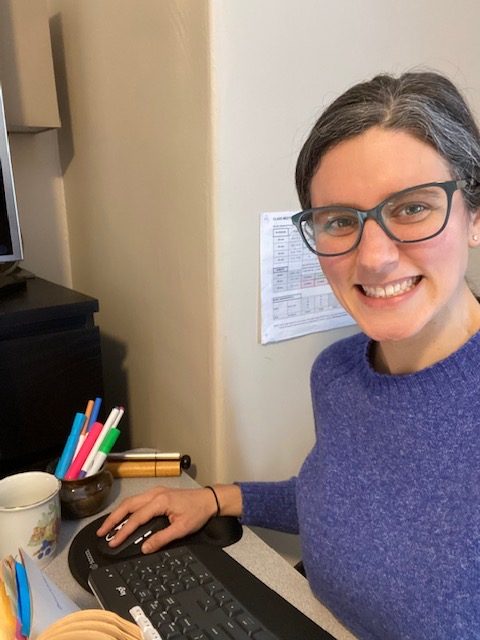

The Remote Teaching Experience

Ms. Garfield is a fully remote English teacher.

As winter break draws near, more and more students have made the choice to switch to Cohort R, and the numbers are steadily rising. Teachers are making accommodations to ensure that these students stay on track with their in-person classmates.

However, this is not the only group of people in the L-S community that does not physically attend school; 29 teachers, roughly 18% of the L-S faculty, have also made the decision to work fully remote. That’s a less-than-insignificant number of educators who have yet to speak to their students face-to-face.

Two of these teachers are Jennifer Garfield and Nathaniel Armistead. They made the decision to go remote primarily due to family concerns, specifically close relatives who are at high risk for COVID-19. An additional factor in Garfield’s decision was uncertainty surrounding her children’s education. “My 3-year-old’s daycare was closed at the time, and they had plans to re-open at full capacity, which I didn’t feel comfortable with,” she explains.

For these faculty members, working entirely over Google Meet is a teaching experience probably unlike any they have had before, and it comes with its own unique challenges.

When teaching fully remote, Armistead’s main concern is connecting with students. “I think it’s way easier for students to fly under the radar if they’re struggling,” he says. To ensure that students remain connected, Armistead makes an effort to have all his students together as a class as much as possible. “I think, with the 9th graders especially, it’s important that they get to know each other,” he adds. Preserving at least some form of connection between students is a priority for Armistead.

This becomes particularly challenging for remote educators during the “in-person” classes, where the students are in the classroom and the teacher is broadcasting on a Google Meet. Since the teacher is not present in the classroom to guide the energy of the class, the nature of these classes can quickly turn stiff and impersonal. Both Garfield and Armistead prefer the all-remote Google Meet classes held in the afternoons to the in-person classes because students can see each other’s faces and they are comfortable in their own homes. “It’s as close to normal as you can get,” says Armistead of the Google Meets.

Despite the disadvantages, teaching from home has its perks. Garfield has found that it is easier to bridge the gap, so to speak, with her students in Cohort R. “I do think I have a better understanding of what the remote students are going through,” she says. With this newfound understanding, Garfield implements movement breaks and screen breaks into her English classes.

There are other ways in which being remote has changed some educators’ teaching methods. In order to fit the limited time that remote teachers have with students this year, Armistead has abridged some of his curriculum to what is most essential. “It’s made me think about what’s necessary and what’s not,” he notes. Remote teachers may also feel the need to make their curriculum more structured than usual so all cohorts stay on track.

All these changes can prove to be very confusing and foreign for students, and Garfield is particularly impressed with how her students are responding. “You all have adapted to this in such an incredible way,” she says.

Even so, a Google Meet cannot perfectly replicate the community that is cultivated at L-S, which many remote teachers miss dearly. “I miss the energy of the classroom,” says Armistead. “Everybody feeds off each other.”

Garfield misses the in-school environment too. “I love walking through the halfway and saying hi to students,” she says, “and you know, just those little mini interactions that make school feel like a home, like a place you belong. I miss those things.”