Reading Banned Books at L-S: the Importance of Diversified Literature

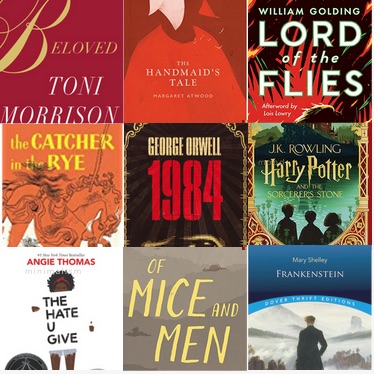

Collage by Julia Minassian

32 states, 138 school districts, 4 million students, 1,648 banned books.

It’s not just books, however. It’s legislation. It’s political violence. It’s erasure on an international scale. Each story deserves a place in our cultural consciousness, but parents, school boards, and lawmakers are banning books at a pace not seen in decades. PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans reports 2,532 instances of individual books being banned from July 2021 to June 2022, censoring 1,648 titles by 1,553 writers, illustrators, and translators. The most prominent foci of books bans typically include books by and/or about LGBTQ+ individuals and people of color.

At L-S, English classes do not shy away from commonly banned books in the US. Of Mice and Men, The Catcher in the Rye, The Hate U Give, The Handmaid’s Tale, 1984, Beloved, Lord of the Flies, and even Harry Potter face bans yet remain staples of L-S classes. Dan Conti, English department coordinator and proud owner of an “I read banned books” T-shirt, explains that the decision on what to teach and how to frame stories are not made haphazardly.

Beginning with the questions “Why are we going to teach this? Why is it important?” the English department takes great responsibility to ensure that students have the opportunity to read diverse stories, allowing them to try on new perspectives. “When we choose literature, we’re not looking to poison people with new ideas or controversy,” Conti explains. “It’s about preparing students to live in an increasingly diverse and complex society.” To some, banned books seem dangerous. The complexity of literature, however, is not a threat to be banned, but rather a concept prompting growth and further exploration of the human experience.

Mike Guanci, another L-S English teacher, explains that, “We live in a pretty liberal part of the country, which is why we haven’t dealt much with book banning.” Consequently, the notion of educational gags and politicized book banning may seem inconceivable, which is even more reason to continue our plight to read diversified literature. “I find that the vast majority of students are very open to different ideas and different viewpoints. I think our community really values that,” Guanci says. He typically receives positive parent feedback on the books/ films he chooses to teach in class. Conti concurs, citing the “immense trust between the English department and the broader community.”

Nevertheless, nuances are evident, and oversimplifying the issue of book banning further fuels political extremism. “What I find unique about this moment in time is that you have questions being raised about books from both ends of the political spectrum,” Conti explains. Left vs. Right and Good vs. Bad are not the extent of the issue. Even those who read the banned books still have their own biases and prejudices. “It’s easy to believe in our own goodness or intelligence over others, and confirmation bias furthers our thoughts of superiority” Guanci explains. The first step to dismantling others’ biases is to dismantle your own, and it is critical that we continue to reevaluate our ideas. At L-S, the English department’s book selection remains fluid, and their curricula change based on new perspectives and guidance. For example, the English department has added new titles in recent years that broadens the diversity and complexity of the human experience, such as Sing, Unburied Sing by Jesmyn Ward, There There by Tommy Orange, and Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu.

Reading provides a gateway to see humanity and deconstruct our biases. “Ultimately, when you read books from different perspectives, it helps you realize that everyone’s just a person,” Guanci says. “Reading someone’s story, it’s difficult to see them as anything less than human.” However, actions to censor literature dissipate opportunities to learn, and we all become less well-rounded thinkers. Mr. Conti stresses that, when students are taught various versions of the truth, we will have less common ground to stand on and respect each other’s humanity. “On a national level, if some states start redacting entire swaths of American history and literature, we will live in a country that has two or more increasingly different stories,” he explains, describing the trend as “deeply troubling and chilling.”

Even if book banning does not directly affect us here at L-S, we need to be fervent advocates for exploring the complexities of literature and willing to try on different points of view. All students deserve to see themselves and understand new perspectives through literature. Conti warns that, if book banning and censorship in education continue and we end up with only one dominant point of view or narrative, “E pluribus unum will only be unum.” The plurality of the world is evident through literature, art, and human nature. Are we going to pretend there’s only unum?